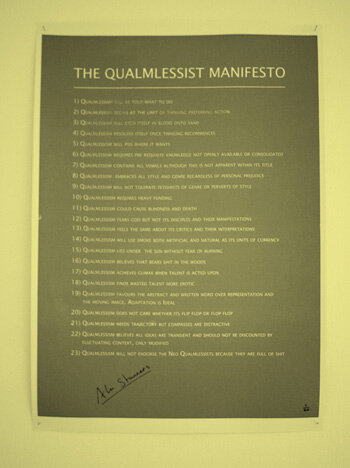

#79 Alan Stanners, The Qualmlessist Manifesto

2 - 21 August

Alan Stanners was born in Dundee. He studied at Glasgow School of Art. Alan currently lives and works where he can.

A conversation between Glen Jamieson and Alan Stanners

Glen Jamieson : I am very pleased to talk with you on the occasion of your solo show and the launch of The Qualmlessist Manifesto at OUTPOST gallery, Norwich. The tone of the manifesto seems both highly sensitive and humorous – an honest and serious satire that responds to the present condition of art, offering artists an alternative to the burdening presence of genre rules and art elitism. Tell me about your decision to write a manifesto. Is the manifesto best described as your ideology as an artist?

Alan Stanners: I think the title goes some way to answer that. ‘Qualmlessim’ as a written word to me sounds severe and almost unintelligible but when spoken phonetically its clumsy, humorous and maybe even more indecipherable. I see it in the same tradition as Duchamps L.H.O.O.Q, a piss take with purpose, except the humour lies not within a hidden message that undermines but within the translation of something visual to something spoken, from one vernacular to another. In other words the absurdity between what we think and what we physically do. The initial catalyst for the manifesto was to create something fluid like a poem; it’s just using the form of a doctrine as a vehicle because it’s nice to be in vogue.

GJ: Your paintings have been described on occasions as a deconstruction of the medium. There are many discernible reference points and enquiries into the qualities of the medium but the paintings are by no means merely a historical site – they appear more self-referential and like the manifesto, concerning the ‘now’. The paintings (for me) place a reader in some kind of human palimpsest; physically there are many layers, with tones of playfulness, humour, and horror. Often a reader is looking for a connection to a human element – a place or a face perhaps. What do you think about when you think about painting? What is it you are looking for?

AS: Firstly, I find deconstruction a bit of a difficult term in the way that it seems retrospective - I prefer reconstruction. You can spend too much time trying to come to terms with what has happened. There have been enough funerals already; the city’s already levelled. I want my work to propose questions about what comes next and how do we go about getting there. On a technical level I prefer abstraction to representational aesthetics in the sense that I believe it comes with less pre ordained cultural baggage. I don’t like telling people what to think, we’re swamped with it as it is. I think that art is a revolt in that sense. All that baggage is there but its up to the individual to decide where they and the work stand within it. I often think about my paintings as being internal, the stuff that lies beneath the surface of the image. If you imagine a portrait with eyes, a nose, any of the usual things you would associate with a face, I like to think my of my pictures as the blood, gristle, bone and muscle that structures that face. My paintings are the physical and cultural gore of my experience on a material, intellectual and sensory level.

GJ: You mentioned earlier about using a vehicle to follow a trajectory in relation to the manifesto. This seems to resonate with your paintings also - perhaps most evident in Auto-Portrait, that takes a vehicle as its vehicle for expression. I am interested as to your choice of vehicle - is Auto-Portrait a self-portrait?

AS: Yeah, I see it as a self-portrait, but also a group portrait because we are all complicit in the situation. I chose the car because it seems the most ubiquitous and as a statement becomes a lowest common denominator, which is something I think we are exposed to on a cultural level at the moment. In terms of narrative I wanted to express an event that is disastrous, the implications of which are devastating but to present it flippantly, comically even. Debasing the seriousness of the event to something entertaining and disposable; replacing steel with plastic. On another level it’s a bit of a pun, Auto-Portrait being a self-portrait as well as literally being a portrait of a car and also a study in autonomous drawing. I like to the think of this picture as an exploded view of a car crash where the constituent elements are not valves and engine components but the mechanical apparatus of painting itself, in the manner of early modern abstractionists such as Kandinsky and Klee.

GJ: On entering the show the first painting that greets the visitor is Qualmlessism. It seems to allure the visitor to the exhibition, with the opportunity for the reader to experience that ‘from one vernacular to the other’ element – ‘something visual to something spoken’. The last thing we see is Blue Swan hung on the rear of the entrance wall. The bright blue appears familiar – like a word, or a calligram to be spoken. With Qualmlessism you are invited to try and read it, indeed the phonetics are a surprise but with Blue Swan the phonetics don’t come – its beauty is disconcerting. If Qualmlessism is the title that invites us to read and consider, is Blue Swan the full stop?

AS: Yeah, in a way I wanted the installation to kind of lead you full circle. Initially when you see Qualmlessim I think you can recognise it as a painting of letters but you’re not sure what it is that you are supposed to be reading. You identify with aspects of it and feel you should understand it, particularly with the “ism”. In Blue swan you see an abstract painting with a symbol that feels recognisable and potentially loaded with content and significance. I think in a way I’m trying to level the playing field prejudice we have between one type of representation and another. In either case be it representation or abstraction, I am not sure.