#100 Andy Parker, PAN-PAN

2 - 26 July

Andy Parker was born in Portsmouth. He studied at The Royal Collage of Art. Andy currently lives and works in London.

A conversation between Andy Parker and Kate Murphy.

Kate Murphy: PAN-PAN is OUTPOST’s 100th show. In response to your initiative to mark the event by making a work with 100 balloons, we’ve organised an after party. The after-ness of things appears central to the work in this exhibition. Your work offers a rare stasis, invoking premonitions of ruin and exhaustive expiry. You referred me to ‘Our Knowledge’, a text by Vilem Flusser where he warns, “The universe of the discourse of science, under unlimited expansion, amputates it’s evaluative and causal dimensions and becomes a formal and empty universe”. Are there parallels to be made with current contemporary practice?

Andy Parker: I’m not sure about being parallel to contemporary practice as I am unavoidably part of it I imagine. My awareness of ruin and expiry - that every new objects renders another obsolete – applies to art as well, and I have a feeling that’s what your pushing me on. I wrote a thesis on art and temporality, and concluded that the art of the gesture was successful at exerting force for change, but that it had to be short lived. Contexts and meanings shifting is a fact of life, so what we see as the ‘art’ in an object now will be far from it’s art-ness in the future. An object has to be willing for these shifts to occur, to become obsolete then re-appropriated or co-opted, or else it has to have it’s own end built in.

KM: There is a play between past and future tense, a quiet doom imbued in the work whereby the future itself is understood in pessimistic past tense. Do you make deliberate the same lack of appeal or outdated quality that there is in the subject, a quality of the work itself?

AP: I’m not sure I consciously use a pessimistic past-tense to describe the future. although it is an appealing phrase. I accept that the future will quickly become past, but any doom for me comes from the relentless repetition of this idea of progress, not the progress itself. The relationship with outdateness that draws my attention to objects flavours each work in its own way, and I’m careful it is not employed as an applied ‘quality’ or effect. The huge roll of waste newsprint I used to make the flag rubbing was given to me as waste by a newspaper printing company. It was ripped from the printing press by someone at the factory and that is the torn edge that remains. The dinks and tears down the side were caused by cycling with it to the ship to do the work, so they provide another formal quality which perhaps adds to this sense of it being a redundant bit of previously functional stuff. It is not acid free, so it will yellow throughout the course of its display too. Although these elements aren’t so deliberate as to be fabricated, the fact they are left is deliberate, part of my decision to take to the shortest line between the work and the world. Who would benefit if the paper were trimmed, cleaned, repaired or framed?

KM: Could you tell me the ‘two printers, two holes’ story?

AP: That sounds filthy. I think you are referring to me moaning about my A3 printer which I can no longer use because the updated operating system on my computer is no longer supported by the printer manufacturer. I believe I was picturing the raw materials for my new printer being dragged from a hole in the earth somewhere, while another hole was dug somewhere else for my old printer to be slung into. It’s an analogy for a poor use of labour if nothing else.

KM: We belong to systems that are beyond our own comprehension; inevitably left behind by them. Flusser elucidates this gap by referring to ‘bad questions’. “The answers we are getting from such questions are becoming ever less satisfactory, and the universe is becoming ever exempt of values and causes… There is no room for wisdom, knowledge progresses absurdly… Everything that interests us, the meaning of life in relation to death, is categorically unknowable since every question that demands such knowledge is a “bad question”. At bottom, that is what we know today: that we can know everything except that which interests us.” Do you ask bad questions?

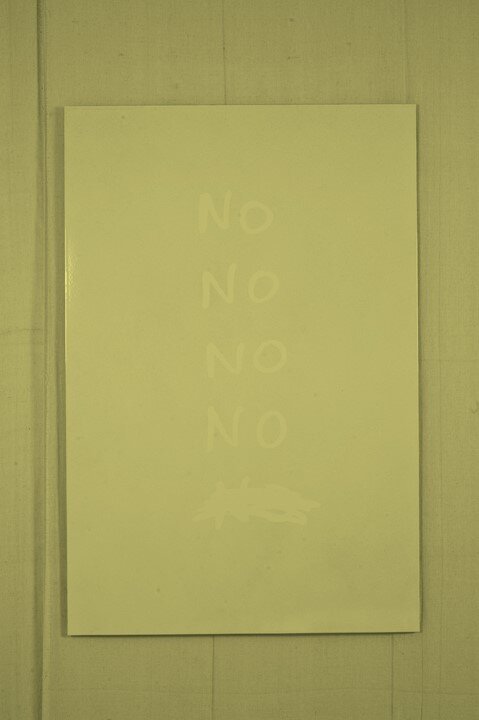

AP: I only just got the Flusser book so I’ve not absorbed it (it has a nice blind emboss on the cover) but my feeling is that we’re trapped between the good and the bad. To poorly paraphrase these two poles, I would say we’re between the wholesale adoption of ‘good’ scientific, formal questions which might be framed as progressive (and have negative connotations for Flusser), and ‘bad’ ideological, causal questions which I guess are regressive. I sense this is what I see enacted in the writing on the vans I photograph and use as the basis of the Dirty Van works - an exploration of the bad, old questions of ‘how one should live’, made in a temporary, public arena with something immediate such as the gesture of a fingertip. There aren’t many spaces left in which to ask these important bad questions, so dirty vehicles are one, and art is another.

KM: In the exhibition other voices resonate through the works. Jan Verwoert, in writing on appropriation suggests, “Ghosts can only speak when the one who summons them speaks too… “In the relationship with a spectre and the one who invokes it, who controls whom will always remain dangerously ambiguous and the subject of practical struggle.” On this subject there is a sense of struggle left evident in the work itself. They appear laboured, or at least studious. Why do you make slow our engagement?

AP: I’ve just been sat in my B&B reading ‘Haunted Norwich’ and I’m quite happy to summon nothing. The Maids Head Hotel over the road has a ghost Chambermaid, and the cellar at Take 5, where the party after the gallery opening is taking place, has a ghostly figure who silently emerges from the plague pit behind its walls. The ghosts of labour present in the work are pedestrian by comparison. ‘Work’ is apparent in the exhibition, but I would hope it doesn’t seem laboured - what is physically present is what it physically took to get there, sometimes that’s a lot and others it’s a little, and often it is mingled with the work and authorship of somebody else. The flag rubbing took about 5 minutes to complete, the gorse paintings took a few weeks. The alterations on the Falklands postcards were somewhere in between - a process of adjustment and repainting to achieve something I was satisfied with. Part of the satisfaction comes from achieving that ‘slow engagement’. When I’m happiest is when I can generate a slow engagement with an art object that results in a slow engagement with something in the world. To return to Mr Verwoerts analogy, I suppose I adopt a position as artist invoking the spectre of the world, and my enjoyment emerges from the ambiguity that can obscure our roles. Did you know there is a ghost called Sarah who haunts No.19 Magdalen Street? She moves objects round inside the building and you used to be able to see her at an upstairs window until they bricked it up.

KM: In what other terms do you like to talk and think about your work?

AP: In my pants, eating pickled onion monster munch. And you?