#60 James McLardy, Common Soul

2 - 21 October

James McLardy was born in Chesterfield, England. He graduated from the Glasgow School of Art in 1999. This is his first solo show in England. McLardy currently lives and works in Glasgow.

A conversation between James McLardy and Elizabeth Ballard, Wednesday 30 September.

Elizabeth Ballard: On your first site visit to OUTPOST, you seemed very taken with the architecture and design of the city. How has this influenced your show Common Soul?

James McLardy: What appealed to me was in the detail – how traditional architectural features, such as weathered beams and eroded stone columns sit with the concrete, metal and the clean white edges of the modern form. When I first visited the gallery I spent some time wandering around the surrounding area observing street encounters between objects and materials. Whether it’s brickwork enveloping ancient lumps of oak or the frame-like glass and steel windows revealing the façade of an older structure within - what interests me is what material is presenting what. Is the organic nature of ye olde feature enhancing the sharp edges of modernity or vice-versa? This form of questioning has definitely had an affect on the development of the work in the show

EB: I’m interested in your use of techniques and materials from modern and industrial to classical and hand crafted process which creates strong contradictions in the works - a bronze appears malleable and weak, and an incredibly detailed, faux marble effect on MDF is totally convincing, yet, am I right in thinking, represents an impossibility?

JM: In part, the contractions in the works have been driven by playing with the various craft processes that have created them. I’m often thinking how one object can highlight something about it’s own production or make comment on it’s differences with another.

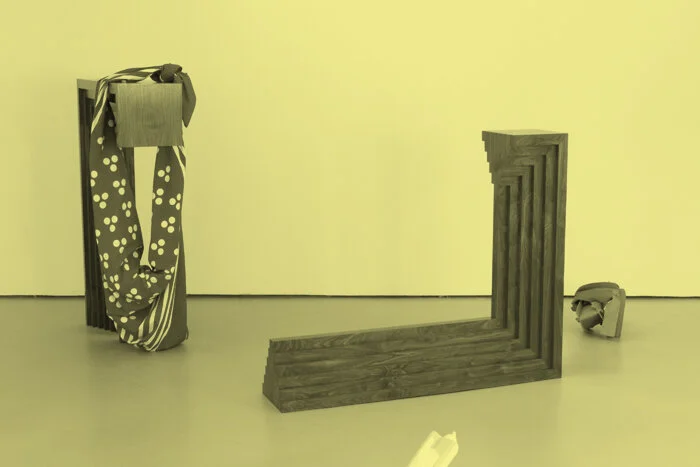

The piece entitled ’Henry’ which, is painted to look like marble represents an impossibility because it’s only 18mm thick, the thickness of a sheet of MDF. I guess it would be pretty extravagant to make something like that in solid marble as you‘d have to waste a massive amount of stone. I like using MDF, because it’s easy to use, but also because it has a kind of folly nature; I mean it’s not really wood either is it?

The bronze piece, entitled Trojan nude is in one way the opposite of the painted MDF as it’s been sandblasted to cloak it’s monumental surface. I began by making the I beam in wax and with a little heat I was able to manipulate it as with clay. The soft flesh-like quality comes from twisting and pinching the wax. This malleable characteristic gives the I beam a sense of vulnerability which was a way to play with the figurative relationship between bronze and classical sculpture.

EB: So where does the giant red neckerchief come from?

JM: This type of neckerchief was something worn by workers, artisans and craftsman in the nineteenth century, so perhaps there is a nod to the arts and crafts there... Although it’s also something you see around today, so it‘s a familiar garment. Perhaps scaling it up makes it a bit comedy but I wanted to disrupt the proportions in the show and counteract some of the minimalist geometry. There is also a thought of the odd personal items of clothing you sometimes see left hanging up on fences and benches around the city.

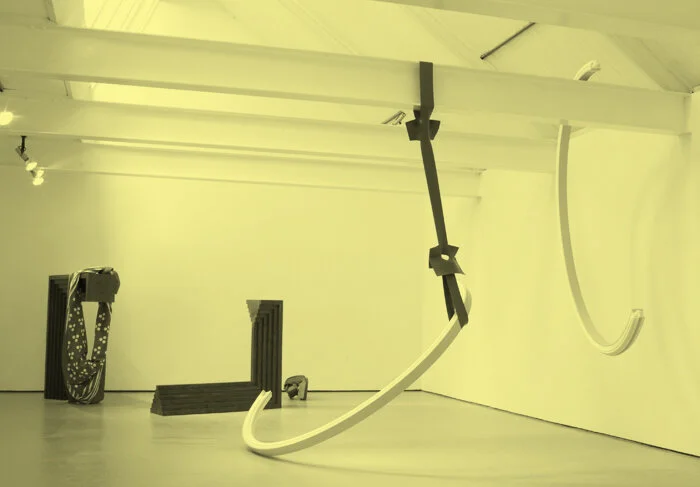

EB: In your work you often borrow architectural motifs yet remain firmly in the realm of sculptural history with the references to Richard Deacon, Sol Le witt, Frank Stella in works such as Strive to set the crooked straight and Before the Fall. These sculptures play with the idea of monument and grandeur, weight and balance yet are incredibly fragile which forces a specific tension within the space.

How significant is the pairing of elements within the works – you have spoken of breaking or smashing works in the past, and so is a sense of fracturing, or separating important to the work?

JM: Strive to make the crooked straight and Before the Fall both make use of the pairing of elements. With the two walnut veneered objects in Strive to make the crooked straight I wanted these elements to appear as though two halves of a large rectilinear object such as a door way or a colossal frame. There’s a sense of magnetism between objects that seem to belong together and I wanted to exploit this to mark and point out a geometric sculptural space between the walnut elements.

In Before the fall there are two hanging semi-elliptical frames made out of painted MDF ‘T’ sections and applied corniced plaster; one form has plaster around the inside and one form has plaster around the outside. I wanted to use the reverse gravity suggested the opposing weight of the plaster profiles to accentuate the looping movement from the gallery floor towards the roof. I was interested in finding ways to imply some of the serpentine dynamic you might expect from sculptors such as Richard Deacon whilst trying to retain their separate autonomy.

I find that fragmenting work leaves more room for your imagination to explore the connections and contrasts across the space. Perhaps there’s something of the Romantic gesture there… of the picturesque ruin.

EB: Well, I’d just like to say James, TOP MARKS!