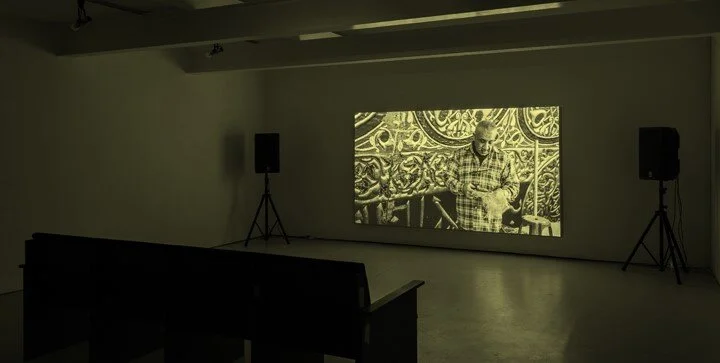

#127 Maeve Brennan, Jerusalem Pink

19 August - 11 September

Maeve Brennan was born in London. She studied at Goldsmiths and Ashkal Alwan’s Home Workspace Program. Maeve currently lives and works in London and Beirut.

A conversation between Marta Bermejo Sarmiento and Maeve Brennan, Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity’s cloister, Norwich, 17 August 2016, early afternoon

Marta Bermejo Sarmiento: It’s interesting how you chose to approach the Dome of the Rock in your film. Very rarely do you get to see a documentary film about this site in which mystical beliefs and religion appear only anecdotally.

Maeve Brennan: I wanted to approach the film from the perspective of material culture, through geology, archaeology, architecture, all of these things that give you a tangible sense of things in Palestine. The Dome of the Rock is usually discussed in symbolic terms, a place for conflict to play out on. I focused on the walls and what it was made of. The fact that the stone is the same material that makes up the landscape, the architecture and the sacred rock. The film documents four experts (an archaeologist, a stone worker, a geologist and an architect) discussing the Palestinian landscape from the perspective of their disciplines. For example, there is this part where the geologist, Dr Taleb al Harithi, says ‘If you blindfold me and drop me anywhere in Palestine, when I wake up I can tell where I am by the stones.’ This was an incredibly important moment because it demonstrated a specific kind of embodied knowledge. He told me that he goes every summer to look for minerals and precious stones on the Palestinian side of the Jordan valley. And because of his knowledge about the shift in tectonic plates he can work out where the same minerals will be deposited on the other side of the valley and goes and collects them there. He travels the exact distance northwards along the valley, following the tectonic shift that occurred. His knowledge of the landscape is a very particular one and it manifests in stones.

MBS: But the religious content doesn’t go completely…

MB: No of course it’s both things and that’s why it’s an interesting site to talk about in this way. I mean I really liked the idea of people coming to the engineer in charge of the building and saying ‘Does the rock float underneath the dome?’ This moment where spirituality or belief in these holy sites comes into contact with the practical maintenance and care for the site.

And of course I don’t answer it directly in the film. But you see the rock at the base of this enormous scaffolding and it becomes a kind of real material space which is being restored, its ornamentation cut up and injected with PVA. I think it’s definitely to do with making things tangible – the building can no longer be seen as a distanced, symbolic object. It is made of lime and marble and it leaks and has dampness. It really … ah, what is the word…

MBS: Materialises?

MB: Yeah sort of, it becomes present as matter. This was my initial interest in geology as well, a material way of thinking through bigger concepts of time and history.

MBS: It seems to me that this film is both an architectural homage to the Dome of the Rock and a homage to the memory of your great grandfather Ernest Tatham Richmond (ETR). How did this come about?

MB: The interest with my great-grandfather began when I found the book he wrote The Dome of the Rock: A Description of its Structure and Decoration (1924). There were these diagrams he’d drawn that depicted the surface of the building. He had used different crosshatches to define the various periods of restoration that had taken place on the exterior walls. They’re really strange images…

I had also been researching the Jerusalem stone industry in Palestine and had filmed a number of quarries. I began to look at those diagrams as documenting a kind of stratigraphy – layers of restoration. The images reminded me of the quarries I had visited, where cuts into the mountains revealed layers of strata, making time visible. That was how it all started with ETR.

It wasn’t a matter of delving into family history in the usual sense. But his role as an architect in charge of the repair and restoration of this building made him relevant to my research. I find the role of the building surveyor really interesting because it gives you a sense that architecture is constantly moving and transforming, not something static. There is this part in ETR’s text where he says that the Dome of the Rock is “alive, almost in the same way a man is alive,” renewing its skin and structure in order to continue existing. With the Dome of the Rock that maintenance becomes a political act because the building is representative of something so significant for Islam and it’s in this contested site. So inscribing those layers of restoration into the surface of the building is kind of like instating a belief in its existence and everything it represents. That’s how he saw it.

MBS: In the film ETR says the Dome of the Rock has been ‘exposed to the destructive attacks of winter storms, earthquakes and “souvenir seekers”’. In Palestine, many souvenirs are charged with belief like pieces of sacred stone. You have chosen to present 300 bespoke lighters, in five different colours.

MB: I think with these sites there is a sense that everyone wants to somehow hold it or have a piece of it. When I first arrived in Jerusalem, my taxi driver was lighting a cigarette and pointed at his lighter which contained an image of the Dome of the Rock and said – ‘Look, Al Aqsa’ [the Palestinian name given to the site]. I’ve always had an interest in these objects that might attempt to condense bigger political, historical or social contexts so the souvenir became pertinent. Much of my work also looks at shifting economies or flows of objects. Jerusalem stone, seatbelts, or in my current research I am looking into a small town in Lebanon that deals mainly in stolen cars and smuggled artefacts from Syria. I wanted to produce an object that would enter into its own flow. The lighter is also particular as it kind of denotes a social encounter, and this is at the basis of all my work.